Jul

07

Posted by jns on 7 July 2008

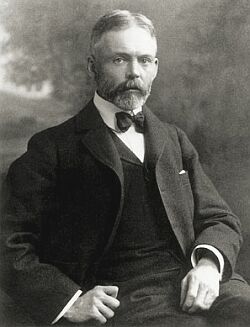

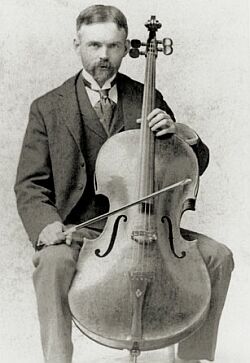

This is geneticist and cellist Edmund Beecher Wilson (1856–1939). On the Columbia University Website, where he is one of their “Living Legacies” (despite his being deceased these last 70 years), he is hailed as the first “cell biologist”, with which history seems agreeable. He spent the bulk of his career at that institution. That “living Legacies” article, “Edmund Beecher Wilson: America’s First Cell Biologist“, by Qais Al-Awqati, is a good appreciation of E.B.Wilson’s work and life, and the source of these two photographs of the younger Wilson.

Early in his research life, just after getting his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins, Wilson became interested in studying the connection between evolution and phylogeny, or phylogenetics (the course of evolution of a species). Later he moved into cell biology and made his greatest discoveries through careful and detailed observation of cell divisions during development, starting with the first division after fertilization of an egg cell by a sperm cell. His work set the course for genetics: the discovery of chromosomes, his own discovery that X and Y chromosomes determine sex (gender), which was a controversial finding at the time, and integrating Mendelian patterns of inheritance into genetics (which wasn’t quite genetics at the time, of course).

Some of this I knew about because I recently finished reading In Pursuit of the Gene : From Darwin to DNA (Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press 2008) by James Schwartz. I liked the book very much, predominantly for these two reasons: 1) it was a thoroughly researched history of the idea of the gene and how it evolved from its earliest (and rather strange) germ of an idea in the theories of Darwin; and 2) author Schwartz actually discussed experiments and their results as a way to comprehend how the idea of the gene made its perilous journey to the modern idea that everyone recognizes and takes for granted. Of course, I wrote a book note.

Even though Schwartz took a biographical approach to telling his story, which he could do largely because the gene-meme almost moved from person to person, as though stepping across a stream on stones, the biographical material were there to serve his main story, that of the idea of the gene. One thing that I did not pick up from Schwartz’ book was Wilson’s love of music, nor the fact that he was a fellow cellist. This is from Qais Al-Awqati’s piece (linked above):

It seems that everybody in Wilson’s family played an instrument. His father played the violin and cello, his mother and sister played the piano (as did both of his aunts), and his brother Charles was a violinist. Wilson began by taking singing lessons, and although he did not have a good singing voice, he says that these lessons left him “with an inveterate habit of reading all of music in do re mi language.” He learned to play the flute, but when he went to Johns Hopkins, he developed a lifelong passion for playing the cello. He wrote, “I was too old to take up so difficult an instrument with any hope of mastering it.” But he eventually became an accomplished cellist and reveled in playing quartets in Bryn Mawr, Philadelphia, and New York.

What a treat: a cute, bearded scientist who was also a cellist! I feel a strange connection across the decades.

Jun

30

Posted by jns on 30 June 2008

This is chemist Richard Willstätter. I confess that his name was not familiar to me despite his having won the 1915 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

This is chemist Richard Willstätter. I confess that his name was not familiar to me despite his having won the 1915 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Here are two short excerpts from his Nobel biography that summarize his prize-winning research.

As a young man he studied [c. 1902] principally the structure and synthesis of plant alkaloids such as atropine and cocaine. In this, as in his later work on quinone and quinone type compounds which are the basis of many dyestuffs, he sought to acquire skill in chemical methods in order to prepare himself for the extensive and more difficult work of investigating plant and animal pigments. [From Munich he went to work in Switzerland for seven years, returning to Germany in 1912, where he took up a position in a newly established Institute of Chemistry in Berlin/Dahlem.]

In the two short years before the outbreak of the first World War he was able with a team of collaborators to round off his investigations into chlorophyll and, in connexion with that, to complete some work on haemoglobin and, in rapid succession, to carry out his studies of anthocyanes, the colouring matter of flowers and fruits. These investigations into plant pigments, especially the work on chlorophyll, were honoured by the award of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry (1915)….

His main achievement, according to the Nobel presentation, was elucidating the chemical nature of the chlorophyll and “having been the first to recognize and to prove with complete evidence the fact that magnesium is not an impurity, but is an integral part of the native, pure chlorophyll – a fact of high importance from the biological point of view (source, the rest of which makes for very interesting reading).” By the way, “Plant Pigments” was the title of Willstätter’s Nobel lecture.

He continued to be productive after winning the prize and worked until he chose to end his career in what must have seemed a startling move.

Willstätter’s career came to a tragic end when, as a gesture against increasing antisemitism, he announced his retirement in 1924. Expressions of confidence by the Faculty, by his students and by the Minister failed to shake the fifty-three year old scientist in his decision to resign. He lived on in retirement in Munich, maintaining contact only with those of his pupils who remained in the Institute and with his successor, Heinrich Wieland, whom he had nominated. Dazzling offers both at home and abroad were alike rejected by him. In 1938 he fled from the Gestapo with the help of his pupil A. Stoll and managed to emigrate to Switzerland, losing all but a meagre part of his belongings.

He lived in Switzerland until he died on 3 August 1942, of a heart attack. I was interested to read that a memorial to Willstätter was unveiled in Muroalto, where he lived his last years, in 1956, the year I was born.

This portrait photograph (source) was taken in 1942 by an unidentified photographer. And now we come to the original reason that Willstätter is the subject of this post, namely so that I could mention that the Smithsonian Institution’s Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology has put some of their large collection of portraits of scientists and inventors online at Flickr: “Portraits of Scientists and Inventors“. This collection has 144 portraits; they tell us that the entire collection is available online in the “Scientific Identity” digital collection.

I first read about the Smithsonian Library’s adding photographs to the Flickr commons project by reading an entry in the Smithsonian Library’s blog. It wasn’t long ago that the Library of Congress delighted fans of photography by putting big chunks of their collections on Flickr in a first-of-its-kind collaboration.

It’s a lot of fun with wonderful images to see; it’s also a great sink of one’s time. But this is culture and heritage and history, right? Besides, I think we’re all better people for knowing more about Richard Willstätter now. What a learning experience is Beard of the Week!

I expect we’ll be exploring more of these portraits in the future.

Jun

24

Posted by jns on 24 June 2008

Yesterday I had a press release from NOAA letting me know that this week, 22-28 June, is “Lightning Safety Awareness Week”. Apparently it is the seventh such declared week. The motto of LSAW comes from the mouth of Leon the Lion: “When Thunder Roars, Go Indoors!”

Yesterday I had a press release from NOAA letting me know that this week, 22-28 June, is “Lightning Safety Awareness Week”. Apparently it is the seventh such declared week. The motto of LSAW comes from the mouth of Leon the Lion: “When Thunder Roars, Go Indoors!”

The National Weather Service, operated by NOAA, maintains a Lightning Safety Website that is filled with useful information and other interesting lightning-awareness stuff. For instance, there is a nice gallery of photographs of lightning, whence came the dramatic photograph at right, taken by Harald Edens near Socorro, NM, 2003 (used by permission).

On the home page, towards the bottom, there is a near real-time map showing lightning strikes in the continental US (and bits north and south) over a two-hour time period (delayed, they say, about 30 minutes after the data were collected).

We learn that each year in the US an average of 62 people are killed by lightning. Of those,

- 98% were outside

- 89% were male

- 30% were males between the ages of 20-25

- 25% were standing under a tree

- 25% occurred on or near the water

We are told that lightning can strike from storms as far away as ten miles, which is why the NWS advises “When Thunder Roars, Go Indoors!” There really are no safe places to be outdoors. Either go inside a “safe building” or get inside a completely enclosed car (with metal roof). A “safe building” has walls with electrical wiring and plumbing, the latter being conductors that can get charge from a lightning strike into the ground instead of into people. Open shelters in parks, for example, are not “safe buildings”. Naturally, there’s more complete information around the NWS website.

Needless to say, perhaps, but my attention was drawn by two pages: “Lightning Science” and “Statistics and More“. Woo hoo!

From “Lightning Science”, lots of fun lightning facts:

- At any given moment, there are 1,800 thunderstorms in progress somewhere on the earth.

-

There are lightning detection systems in the United States and they monitor an average of 25 million flashes of lightning from the cloud to ground every year!

- Ice crystals in a cloud seem necessary lightning, which may result from charge separation that takes place in collisions of ice crystals.

- Lightning is a rather complicated process for discharging negative charge in the cloud.

“Statistics and More” has several interesting sounding things like interesting lightning events in history, details on lightning deaths, policy statements, factsheets, and guidelines. Links can be so much fun sometimes.

My own awareness was increased this week by the rather dramatic thunderstorms we had last Sunday night, and again on Monday night, when Isaac and I were out and we both saw a brilliant stroke of lightning.

Jun

19

Posted by jns on 19 June 2008

This news from NASA and the Phoenix Mars Lander seems to be traveling around with near light speed:

Bright Chunks at Phoenix Lander’s Mars Site Must Have Been Ice 06.19.08

TUCSON, Ariz. – Dice-size crumbs of bright material have vanished from inside a trench where they were photographed by NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander four days ago, convincing scientists that the material was frozen water that vaporized after digging exposed it.

“It must be ice,” said Phoenix Principal Investigator Peter Smith of the University of Arizona, Tucson. “These little clumps completely disappearing over the course of a few days, that is perfect evidence that it’s ice. There had been some question whether the bright material was salt. Salt can’t do that.”

The chunks were left at the bottom of a trench informally called “Dodo-Goldilocks” when Phoenix’s Robotic Arm enlarged that trench on June 15, during the 20th Martian day, or sol, since landing. Several were gone when Phoenix looked at the trench early today, on Sol 24.

[more]

Of course this is big news for the mission and everyone watching it. Finding evidence of water* on Mars–even evidence of water ever having been on Mars–is usually taken as a necessary condition for finding evidence of any life existing, or having existed at one time, on Mars. Whether this is really true is another matter, but water played a necessary role for life to appear on Earth so it’s thought that no water would mean no chance of life.

Now we believe that there is currently frozen water, existing now, today, on Mars. It doesn’t mean extraterrestrial life but a serious road-block (i.e., no water) has been removed. Besides, discovering signs of water, either now or ever, has been a long, long quest for a good number of people, and now they’ve found it.

A lot of people are pretty excited.

__________

* The evidence: four days ago Phoenix was digging a trench when it came upon a solid, white layer. The layer could have been frozen water or maybe something like salt. What’s happened in the last four days? Some small chunks of the white substance, loosened when Phoenix was digging, disappeared. Disappearing means evaporating (more precisely, “sublimating”, which is the word that means evaporating directly from the solid form without first melting), something that salt and other likely substances would emphatically not do, whereas exposed water ice would do exactly that.

Jun

12

Posted by jns on 12 June 2008

Last week I finished reading Janet Lembke’s, Despicable Species : On Cowbirds, Kudzu, Hornworms, and Other Scourges (New York : The Lyons Press, 1999. xi + 216 pages, illustrations by Joe Nutt). You might like to read my book note about it.

I like the author’s portrait inside the back cover: the gracefully maturing lady with her white hair in a bun and the tiny grin of mischief on her face. She’s one of Miss Marple’s friends who invites the lady detective to tea and talks about bugs. How charming! Or–wait!–maybe she’s the murderess and there’s arsenic in the brew.

Ms. Lembke writes with a certain genteel prose but there’s nothing soft about her subjects and her writing is fully informed by science despite her blurb’s insistence that she is, basically, a literary type. However, I don’t see why Shakespeare and taxonomic nomenclature shouldn’t get along as she so aptly demonstrates. These essays about those plants and animals most hated by her friends were charming but robust, personal but informative. Be delighted and learn: what a concept!

Here I wanted to share this little poem that Lembke quoted in the essay “Legs: Centipedes”.

The centipede was happy quite

Until a toad in fun

Said, “Pray, which leg comes after which?”

That worked her mind to such a pitch,

She lay distracted in a ditch,

Considering how to run.

– Mrs. Edward Caster, 1871

Jun

01

Posted by jns on 1 June 2008

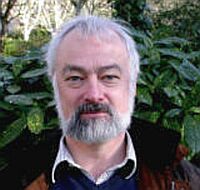

The beard at right belongs to author Wallace Arthur, Professor of Zoology at the National University of Ireland, Galway. I recently read his excellent book Creatures of Accident : The Rise of the Animal Kingdom (New York, Hill and Wang, 2006. x + 255 pages). Naturally, there’s a book note, with a couple of entertaining excerpts. The book, by the way, has its own website.

The beard at right belongs to author Wallace Arthur, Professor of Zoology at the National University of Ireland, Galway. I recently read his excellent book Creatures of Accident : The Rise of the Animal Kingdom (New York, Hill and Wang, 2006. x + 255 pages). Naturally, there’s a book note, with a couple of entertaining excerpts. The book, by the way, has its own website.

This is the second book* I’ve read about evo-devo: “evolutionary developmental biology”, sort of embryology informed by genetics and microbiology. Cool stuff, cutting edge, and learning some about it clarifies an unusual amount of evolutionary concepts for me. One key idea is that evolution doesn’t operate on adult animals, it operates on developing embryos. That small shift in perspective sheds a lot of light.

Author Arthur takes a delightfully cozy and intimate tone in his book, which I thought was almost like an expanded personal essay at times, and very enjoyable for it. Arthur managed to avoid a number of possibly intimidating details in pursuit of focusing on some central concepts over which he lingered a bit to avoid leaving any readers behind. I thought he did a great job and I enjoyed the book quite a bit. I also didn’t mind having a peek at the author’s photo inside the back cover occasionally, either.

Arthur set out to write without revealing his biases towards big questions about creation and whether a who or what was responsible for it, and he managed quite well until he got to his chapter called “Big Questions”, when he finally revealed himself. The preceding parts of the book had been so gentle that I was a bit surprised by his vehemence, although I wouldn’t argue with it in the least.

To research this chapter ["Big Questions"], I did something I had never done before: I visited some Web sites representing creationism in its many guises. This exercise was a revelation indeed, but probably not of the sort that the Webmasters had intended. What I found most striking was the appalling lack of integrity of those concerned. The deliberate misuse of quotations and details from the work of scientists suggested that all honor and honesty had been cast to the four winds. I realized that I was in a different social context from the one I have known and loved for my whole scientific career, where an honest search for the truth is at the heart of things. Instead, I was in a milieu where the dominant ethos was to force acceptance of a particular worldview by any means whatever. No holds barred. not the Spanish Inquisition perhaps, but the intention seemed the same; to stifle freedom of thought. And it mattered not whether I was in the grips of young-earth creationists or intelligent-design proponents. The latter were more slippery and difficult to pin down, but always in the end I found evidence of dishonesty. [p. 226]

__________

* The first, which I got very excited about, was Sean Carroll’s Endless Forms Most Beautiful.

May

23

Posted by jns on 23 May 2008

In truth it was last summer* when I read the book by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus : The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York : Vintage Books, 2005; 721 pages). It’s only today, however, when I finally got around to assembling my notes into the requisite book note.

It’s a magnificent, informative, and very readable book about a central figure of the last century, the contradictory J. Robert Oppenheimer. Knowing what went on with the Manhattan Project and then the persecution of Oppenheimer may well be required knowledge for good American citizenship; reading this book would be a terrific way to get up to speed on that. (Coupled with Richard Rhodes’The Making of the Atomic Bomb, you can learn virtually all you need to know from two excellent books.)

Guess what? I had some left-over quotations I wanted to excerpt, so there they are.

As Harry Truman moved into the White House, the war in Europe was nearly won. But the war in the Pacific was coming to its bloodiest climax. On the evening of March9–10, 1945, 334 B-29 aircraft dropped tons of jellied gasoline–napalm–and high explosives on Tokyo. The resulting firestorm killed an estimated 100,000 people and completely burned out 15.8 square miles of the city. The fire-bombing raids continued and by July 1945, all but five of Japan’s major cities had been razed and hundreds of 1945, all but five of Japan’s major cities had been razed and hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians had been killed. This was total warfare, an attack aimed at the destruction of a nation, not just its military targets.

The fire bombings were no secret. Ordinary Americans read about the raids in their newspapers. Thoughtful people understood that strategic bombing of cities raised profound ethical questions. “I remember Mr. Stimson [the secretary of war] saying to me,” Oppenheimer later remarked, “that he thought it appalling that there should be no protest over the air raids which we were conducting against Japan, which in the case of Tokyo led to such extraordinarily heavy loss of life. He didn’t say that the air strikes shouldn’t be carried on, but he did think there was something wrong with a country where no one questioned that….”

On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler committed suicide, and eight days later Germany surrendered. When Emilio Segrè heard the news, his first reaction was, “We have been too late.” Like almost everyone at Los Alamos, Segrè thought that defeating Hitler was the sole justification for working on the “gadget.” “How that the bomb could not be used against the Nazis, doubts arose,” he wrote in his memoirs. “Those doubts, even if they do not appear in official reports, were discussed in many private discussions.” [p. 291]

One of the big reasons for developing the Bomb, at least in the minds of the scientists, was to do it before Hitler’s scientists did, lest the world suffer the consequences. The military and the US Government, on the other hand, had a different agenda and insisted on using the bomb on an actual target even thought the Japanese were close to surrender, perhaps as a demonstration to the Soviet Union. The atomic-project scientists felt betrayed and suddenly conflicted as that realization dawned. The whole affair is murky and filled with intrigue.

There was much that Oppenheimer did not know. As he later recalled, “We didn’t know beans about the military situation in Japan. We didn’t know whether they could be caused to surrender by other means or whether the invasion was really inevitable. But in the backs of our minds was the notion that the invasion was inevitable because we had been told that.” Among other things, he was unaware that military intelligence in Washington had intercepted and decoded messages from Japan indicating that the Japanese government understood the war was lost and was seeking acceptable surrender terms.

On May 28, for instance, Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy urged Stimson to recommend that the term “unconditional surrender” be dropped from America’s demands on the Japanese. Based on their reading of intercepted Japanese cable traffic (code-named “Magic’). McCloy and many other ranking officials could see that key members of the Tokyo government were trying to find a way to terminate the war, largely on Washington’s terms. On the same day, Acting Secretary of State Joseph C. Grew had a long meeting with President Truman an told him the very same thing. Whatever their other objectives, Japanese government officials had one immutable condition, as Allen Dulles, then an OSS agent in Switzerland, reported to McCloy: “They wanted to keep their emperor and the constitution, fearing that otherwise a military surrender would only mean the collapse of all order and of all discipline.”

On June 18, Truman’s chief of staff, Adm. William D. Leahy, wrote in his diary: “It is my opinion at the present time that a surrender of Japan can be arranged with terms that can be accepted by Japan….” The same day, McCloy told President Truman that he believed the Japanese military position to be so dire as to raise the “question of whether we needed to get Russia in to help us defeat Japan.” He went on to tell Truman that before a final decision was taken to invade the Japanese home islands, or to use the atomic bomb, political steps should be taken that might well secure a full Japanese surrender. The Japanese, he said, should be told that they “would be permitted to retain the Emperor and a form of government of their own choosing.” In addition, he said, “the Japs should be told, furthermore, that we had another and terrifyingly destructive weapon which we would have to use if they did not surrender.”

According to McCloy, Truman seemed receptive to these suggestions. American military superiority was such that by July 17 McCloy was writing in his diary: “The delivery of a warning now would hit them at the moment. It would probably bring what we are after–the successful termination of the war.”

According to Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, when he was informed of the existence of the bomb at the Potsdam Conference in July, he told Stimson he thought an atomic bombing was unnecessary to hit them with that awful thing.” Finally, President Truman himself seemed to think that the Japanese were very close to capitulation. Writing in his private, handwritten diary on July 18, 1945, the president referred to a recently intercepted cable quoting the emperor to the Japanese envoy in Moscow as a “telegram from Jap Emperor asking for peace.” The cable said: “Unconditional surrender is the only obstacle to peace….” Truman had extracted a promise from Stalin that he and many of his military planners thought would be decisive. “He’ll [Stalin] be in the Jap war on August 15,” Truman wrote in his diary on July 17. “Fini Japs when that comes about.”

Truman and the men around him knew that the initial invasion of the Japanese home islands was not scheduled to take place until November 1, 1945–at the earliest. And nearly all the president’s advisers believed the war would be over prior to that date. It would surely end with the shock of a Soviet declaration of war–or it might end with the kind of political overture to the Japanese that Grew, McCloy, Leahy and many others envisioned: a clarification of the terms of surrender to specify that the Japanese could keep their emperor. But Truman–and his closest adviser, Secretary of State James F. Byrnes–had decided that the advent of the atomic bomb gave them yet another option. As Byrnes later explained, “…it was ever present in my mind that it was important that we should have an end to the war before the Russians came in.”

Short of a clarification of the terms of surrender–a move Byrnes opposed on domestic political grounds–the war could end prior to August 15 only with the use of the new weapon. Thus, on July 18, Truman noted in his diary, “Believe Japs will fold up before Russia comes in.” Finally, on August 3, Walter Brown, a special assistant to Secretary Byrnes, wrote in his diary: “President, Leahy, JFB [Byrnes] agreed Japs looking for peace. (Leahy had another report from the Pacific.) President afraid they will sue for peace through Russia instead of some country like Sweden.” [pp. 3000--301]

__________

* In fact it was the book I took with me on our trip in July 2007 to Tuscany. I have fond memories of lying in bed in our hotel room in Pisa reading about Oppenheimer.

May

23

Posted by jns on 23 May 2008

I recently finished reading Richard Dawkins’ Climbing Mount Improbable (New York : W.W.Norton & Company, 1996, 340 pages). It wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t his best by any means. All of the little things that irritate me about Dawkins’ writing seemed emphasized in this book. There’s more in my book note, of course.

Dawkins is usually such a careful writer so I was surprised by the brief lapse of analytical perspicacity he exhibits in this passage. He is describing the fascinating compass termites that build tall and surprisingly flat mounds, like thin gravestones.

They are called compass termites because their mounds are always lined up north-south–they can be used as compasses by lost travellers (as can satellite dishes, by the way: in Britain they seem all to face south). [p. 17]

Well, of course they seem to face south–the satellite dishes, I mean–and there’s a very good reason. I can’t believe Dawkins would say something this…well, I can’t think of just the right word to combine unthinking lapses with scientific naiveté, specially since he’s the Charles Simony Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford. Tsk.

Satellite dishes are reflectors for radio waves transmitted by satellites; the dishes are curved the way they are so that they focus the radio signal at the point in front of the dish where the actual receiver electronics reside, usually at the top of a tripod arrangement of struts. In order to do this effectively the satellite dish must point very precisely towards the satellite whose radio transmitter it is listening to.

If the satellite-radio dish is stationary, as most are, that means that the satellite itself appears stationary. In other words, the satellite of interest always appears at the same, unmoving point in the sky relative to the satellite dish, fixed angle up, fixed angle on the compass.

Such satellites are called “geostationary” for the obvious reason that they appear at stationary spots above the Earth. In order to appear stationary, the satellites must rotate at the same angular velocity as the Earth, and they must appear not to move in northerly or southerly directions.

In order not to appear to move north or south, and to have a stable orbit, the satellites must be positioned directly above the Earth’s equator (i.e., in the plane that passes through the Earth’s equator). In order to have the necessary angular velocity they must be at an altitude of about 35,786 km, but that detail isn’t terribly important for this purpose.

Armed with these facts, we may now consider two simple questions, the answers to which apparently eluded Mr. Dawkins:

- For an observer in Great Britain, in what direction is the equator?

- If a satellite dish in Great Britain wishes to listen to a geostationary satellite, in which direction will it point?

The answers: 1) south; and 2) southerly.* Now it’s no surprise that (virtually) all satellite dishes in Britain do point south.

———-

* Yes, there are slight complications having to do with the longitude of the particular satellite, but most of interest to Great Britain will be parked near enough to 0° longitude not to affect the general conclusion.

May

13

Posted by jns on 13 May 2008

I recently finished reading Simon Winchester’s excellent book, The Map that Changed the World : William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology (New York : HarperCollins, 2001, 329 pages). It’s the fascinating story of William Smith (1769—1839) and how he came to draw the first geological map of England (the first in the world, actually), how he came to be mistreated by the Geological Society of London, largely because of his class, the profound influence he had on the just forming science of geology, and how he finally got the recognition he deserved. It’s quite a human and intellectual adventure. My book note is here.

At least my four regular readers will be aware that I have a fascination for footnotes. The author of this book, Simon Winchester, seemed to be a man after my own heart. Here are two charming and informative footnotes from the book.

*A guinea, equivalent to a pound and a shilling, is a classically British and very informal unit of currency–with neither a coin nor a bill to formalize it–that is still used today (despite Britain’s having adopted decimal currency in 1971) in some circles, such as the buying and selling of racehorses and sheep. There used to be a one-guinea coin, struck from gold from the eponymous nation, but only its name and worth survive, and today the word is only a vague and ephemeral throwback to more casual financial times. [first footnote on page 61]

†This appears to be the first time that William Smith uses a term deriving from the word strata, the study of which would so dominate his life as to become his nickname: To all nineteenth-century England he would be simply Strata Smite. The OED suggests that the words stratum and strata, meaning a layer or layers of sedimentary rock, became current in England at the end of the seventeenth century; Smith himself was the first to use stratigraphical in 1817; stratification made its first appearance in 1795. [footnote on page 65]

May

08

Posted by jns on 8 May 2008

For a few days recently I was reading Simon Singh’s book, Fermat’s Enigma : The Quest to Solve the World’s Greatest Mathematical Problem (New York : Walker and Company, 1997, 315 pages). However, I stopped reading after about 80 pages.

The reason had nothing to do with the subject, which was interesting and developing reasonably well. Finding out more about Fermat, his work and his life and his time, and learning some about the man who has apparently proved Fermat’s notorious “last theorem” (Wikipedia on Fermat’s Last Theorem can fill you in on those details if you want) was all to my liking.

What was not to my liking was Singh’s writing. It was writing that was too loose, too flabby when dealing with subjects that I feel require more precision in their presentation. Writing a popular treatment about a mathematical or scientific subject is no time for technically sloppy or carelessly inaccurate prose. Writing for the scientifically or technically unsophisticated reader demands care. I’m sure you’re aware by now that this is an idée fixe for me, and for Ars Hermeneutica.

There were no major transgressions but a pile-up of minor infractions to the point that it was irritating. Let’s look at a few examples.

Mathematical theorems rely on this logical process [of proof] and once proven are true until the end of time. Mathematical proofs are absolute. To appreciate the value of such proofs they should be compared with their poor relation, the scientific proof. [p.21]

In one sense you could say that once proven mathematical theorems are true, in the sense that once proven they stayed proved. However, the sentence is sloppy and ambiguous as a result, suggesting that perhaps the theorem was not true before it was proven.

That is not the way mathematicians look at theorems and proofs, however. Theorems are seen more as emergent truths of a mathematical system, statements that have always existentially true but unknown to be true before they are discovered and their truth established by means of proof.

It’s akin to finding a rock and saying “I recognize this as a sedimentary rock, so it will henceforth be a sedimentary rock.” Most of us would look askance at such a statement with the obvious reaction: “Wasn’t it always a sedimentary rock, even before anyone saw it?”

Arguing in the author’s favor, I suspect that he didn’t mean his sentence this way; rather, he wanted to make the point that once the truth of a theorem is established by proof, that proof remains valid unless an error is discovered in the proof or some problem is discovered in the mathematical system in which the theorem and proof is embedded. However, that’s not what he wrote.

As for that bit about “their poor relation, the scientific proof”–it will take at least another entire essay for me to deal with the issues raised by that “poor relation” jibe (it doesn’t upset me that much) and the lack of understanding surrounding the reference to “scientific proof” (that does upset me quite a bit).

Together Fermat and Pascal would discover the first proofs and cast-iron certainties in probability theory, a subject that is inherently uncertain. [p. 40]

Yikes! According to the book-jacket, Mr. Singh has an advanced degree in particle physics. A great deal of experimental particle physics means looking at decay products of high-energy nuclear interactions, processes that are governed by probabilities. Exact probabilities in many cases. He should know better than to write that probability theory is “inherently uncertain.” Probability theory is a mathematical discipline with exact results, and those exact results describe processes that are inherently uncertain. To ascribe “inherent uncertainty” to a discipline whose subject is “inherent uncertainty” is naive and/or thoughtless, and does nothing here to keep the unsophisticated reader from getting confused.

Fermat’s panoply of theorems ranged from the fundamental to the simply amusing. Mathematicians rank the importance of theorems according to their impact on the rest of mathematics. [p. 66]

I simply found this statement bizarre, suggesting as it does that there are mathematicians someplace whose job it is to rank the importance of theorems to the world of mathematics. Do they have a list they check against? Where do they publish their list of theorems, ordered by importance?

Of course Mr. Singh is talking figuratively, looking for an “objective” way to describe the importance of Fermat’s theorem, but he does it again with sloppy writing that suggests something quite other than what he intended.

Instances like these kept cropping up and their irritation overwhelmed me by around page 80. I knew by then that I wouldn’t enjoy reading the book and it didn’t even seem worth the bother of finishing so that I could write a negative book note–I much prefer guiding potential readers towards good books rather than away from bad books.

Part of my professional mission, though, is to consider how we (the big “we” of those who write science for general consumption) communicate science, and how we can communicate it better. Sometimes that means looking at examples of miscommunication so that we can improve. Think of is as an engineering approach (as Henry Petroski does in his excellent books) in which failure has much to tell us about how to succeed.

This is chemist Richard Willstätter. I confess that his name was not familiar to me despite his having won the 1915 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

This is chemist Richard Willstätter. I confess that his name was not familiar to me despite his having won the 1915 Nobel Prize in chemistry. Yesterday I had a

Yesterday I had a  The beard at right belongs to author Wallace Arthur,

The beard at right belongs to author Wallace Arthur,