Apr

28

Posted by jns on

April 28, 2009

Via Joe.My.God I learn that a new CBS News / New York Times poll shows an amazing 42% of those polled in favor of legal marriage for same-sex couples. That’s amazing because the previous poll by the same group only one month ago found only 33% in favor of legal marriage. This increase of 9 points lies well outside the sampling error of the poll and must represent some significant fall-out from the addition of Iowa and Vermont to the growing list of states with marriage equality.

That’s interesting enough, but this graphic from CBS (source for graphic and poll results) is also interesting:

One thing to note is that fully two-thirds of those polled support some sort of legal recognition for same-sex couples.

The other thing to note is that there is a 5% wedge missing from the pie chart. Add up the percentages and you get 95%. Now, while it is not at all unusual to have some 5% of those asked who are undecided or who wish to give no opinion, it is not kosher to leave them out of the pie chart and sort of fudge the other wedges around to fill in the space.

Does this chart make it clear that there is a 5% wedge unaccounted for? Not at all. Somehow the wedges are made to look as though they fill 100% of the circle and yet they should not. You might think that 5% is small and wouldn’t be visible, but it amounts to one-fifth of the “civil unions” wedge, an amount that would be quite noticeable. So, the chart is inaccurate and misleading. I wonder which wedge, or wedges, got the undecideds?

Shame on CBS. I hate it when big corporations who could have science and math consultants without even noticing the cost can’t be bothered.

—–

[Updated a few minutes later:] In thinking about the poll results and the remarkable shift since the previous poll, Timothy Kincaid at Box Turtle Bulletin (“Americans Shift Sharply in Favor of Marriage“) gives a long list of significant steps that have been taken towards marriage equality in the interval between the polls.

Apr

08

Posted by jns on

April 8, 2009

Last week (on 4 April 2009, to be precise), this item came from SpaceWeather.com:

SPOTLESS SUNS: Yesterday, NASA announced that the sun has plunged into the deepest solar minimum in nearly a century. Sunspots have all but vanished and consequently the sun has become very quiet. In 2008, the sun had no spots 73% of the time, a 95-year low. In 2009, sunspots are even more scarce, with the “spotless rate” jumping to 87%. We are currently experiencing a stretch of 25 continuous days uninterrupted by sunspots–and there’s no end in sight.

This is a big event, but it is not unprecedented. Similarly deep solar minima were common in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, and each time the sun recovered with a fairly robust solar maximum. That’s probably what will happen in the present case, although no one can say for sure. This is the first deep solar minimum of the Space Age, and the first one we have been able to observe using modern technology. Is it like others of the past? Or does this solar minimum have its own unique characteristics that we will discover for the first time as the cycle unfolds? These questions are at the cutting edge of solar physics.

There was a notable period of near sun-spotless activity between 1645 and 1715 known as the Maunder Minimum. There is a description in my posting “On Reading The Little Ice Age“.

The Maunder Minimum more or less coincided with one long cooling period in Europe, making it a darling of climate-change deniers who naively want to blame every climate shift on changes in solar activity.

What dire warnings will accompany the realization of the current solar minimum? Will the threatened climate disasters rival those due to god’s wrath over gay marriage? Only time will tell.

Apr

02

Posted by jns on

April 2, 2009

This is physicist and science-fiction author Gregory Benford. His official website, source of the photograph, tells us that

This is physicist and science-fiction author Gregory Benford. His official website, source of the photograph, tells us that

Benford [born in Mobile, Alabama, on January 30, 1941] is a professor of physics at the University of California, Irvine, where he has been a faculty member since 1971. Benford conducts research in plasma turbulence theory and experiment, and in astrophysics.

Around 1990, the last time I was on a sci-fi binge, I read a number of his books; I see from the official list of novels that I’m behind by a number of books. I should pick up where I left off. I remember Benford’s writing as being very satisfactory from both a science viewpoint and from a fiction viewpoint, although I find that, in my mind, I confuse some of the story-memory details with plots by the late physicist and sci-fi author Charles Sheffield, to whom I give the edge in my preference for hard-science-fiction and adventuresome plots.

But, as is not unprecedented in this forum, Mr. Benford is really providing a pretext–a worthwhile pretext on several counts, clearly, but a pretext nonetheless, because I wanted to talk about “Benford’s Law” and that Benford did not wear a beard.

Frank Benford (1883-1948) was a physicist, or perhaps an electrical engineer–or perhaps both; sources differ but the distinctions weren’t so great in those days. His name is attached to Benford’s Law not because he was the first to notice the peculiar mathematical phenomenon but because he was better at drawing attention to it.

I like this quick summary of the history (Kevin Maney, “Baffled by math? Wait ’til I tell you about Benford’s Law“, USAToday, c. 2000)

The first inkling of this was discovered in 1881 by astronomer Simon Newcomb. He’d been looking up numbers in an old book of logarithms and noticed that the pages that began with one and two were far more tattered than the pages for eight and nine. He published an article, but because he couldn’t prove or explain his observation, it was considered a mathematical fluke. In 1963, Frank Benford, a physicist at General Electric, ran across the same phenomenon, tried it out on 20,229 different sets of data (baseball statistics, numbers in newspaper stories and so on) and found it always worked.

It’s not a terribly difficult idea, but it’s a little difficult to pin down exactly what Benford’s Law applies to. Let’s start with this tidy description (from Malcolm W. Browne, “Following Benford’s Law, or Looking Out for No. 1“, New York Times, 4 August 1998):

Intuitively, most people assume that in a string of numbers sampled randomly from some body of data, the first non-zero digit could be any number from 1 through 9. All nine numbers would be regarded as equally probable.

But, as Dr. Benford discovered, in a huge assortment of number sequences — random samples from a day’s stock quotations, a tournament’s tennis scores, the numbers on the front page of The New York Times, the populations of towns, electricity bills in the Solomon Islands, the molecular weights of compounds the half-lives of radioactive atoms and much more — this is not so.

Given a string of at least four numbers sampled from one or more of these sets of data, the chance that the first digit will be 1 is not one in nine, as many people would imagine; according to Benford’s Law, it is 30.1 percent, or nearly one in three. The chance that the first number in the string will be 2 is only 17.6 percent, and the probabilities that successive numbers will be the first digit decline smoothly up to 9, which has only a 4.6 percent chance.

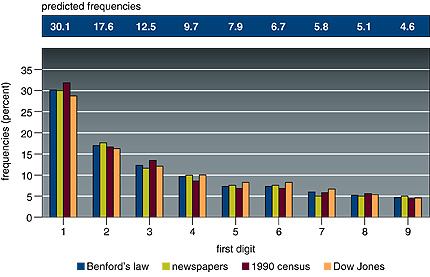

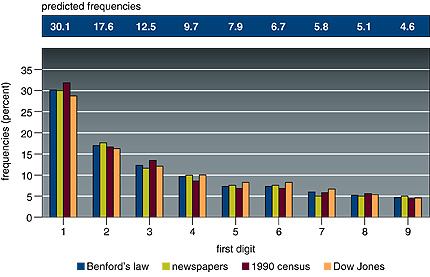

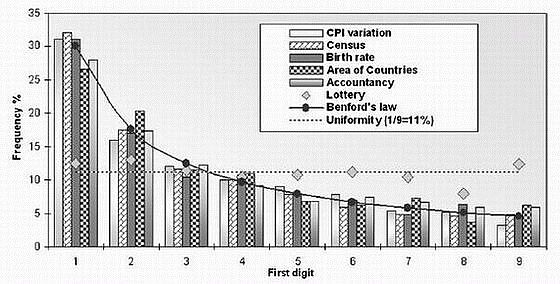

Take a long series of numbers drawn from certain broad sets, and look at the first digit of each number. The frequency of occurrence of the numerals 1 through 9 are not uniform, but distributed according to Benford’s Law. Look at this figure that accompanies the Times article:

Here is the original caption:

(From “The First-Digit Phenomenon” by T. P. Hill, American Scientist, July-August 1998)

Benford’s law predicts a decreasing frequency of first digits, from 1 through 9. Every entry in data sets developed by Benford for numbers appearing on the front pages of newspapers, by Mark Nigrini of 3,141 county populations in the 1990 U.S. Census and by Eduardo Ley of the Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1990-93 follows Benford’s law within 2 percent.

Notice particularly the sets of numbers that were examined for the graph above: numbers from newspapers (not sports scores or anything sensible, just all the numbers from their front pages), census data, Dow Jones averages. These collections of numbers do have some common characteristics but it’s a little hard to pin down with precision and clarity.

Wolfram Math (which shows a lovely version of Benford’s original example data set halfway down this page) says that “Benford’s law applies to data that are not dimensionless, so the numerical values of the data depend on the units”, which seems broadly true but, curiously, is not true of the original example of logarithm tables. (But they may be the fortuitous exception, having to do with their logarithmic nature.)

Wikipedia finds that a sensible explanation can be tied to the idea of broad distributions of numbers, a distribution that covers orders of magnitude so that logarithmic comparisons come into play. Plausible but not terribly quantitative.

This explanation (James Fallows, “Why didn’t I know this before? (Math dept: Benford’s law)“, The Atlantic, 21 November 2008) serves almost as well as any without going into technical details:

It turns out that if you list the population of cities, the length of rivers, the area of states or counties, the sales figures for stores, the items on your credit card statement, the figures you find in an issue of the Atlantic, the voting results from local precincts, etc, nearly one third of all the numbers will start with 1, and nearly half will start with either 1 or 2. (To be specific, 30% will start with 1, and 18% with 2.) Not even one twentieth of the numbers will begin with 9.

This doesn’t apply to numbers that are chosen to fit a specific range — sales prices, for instance, which might be $49.99 or $99.95 — nor numbers specifically designed to be random in their origin, like winning lottery or Powerball figures or computer-generated random sums. But it applies to so many other sets of data that it turns out to be a useful test for whether reported data is legitimate or faked.

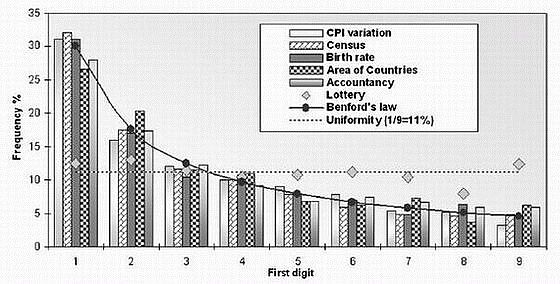

Here’s yet another graph of first digits from vastly differing sets numbers following Benford’s Law (from Lisa Zyga, “Numbers follow a surprising law of digits, and scientists can’t explain why“, physorg.com, 10 May 2007); again one should note the extreme heterogeneity of the number sets (they give “lottery” results to show that, as one truly wants, the digits are actually random):

The T.P. Hill mentioned above (in the caption to the first figure), is a professor of mathematics at Georgia Tech who’s been able to prove some rigorous results about Benford’s Law. From that institution, this profile of Hill (with an entertaining photograph of the mathematician and some students) gives some useful information:

Many mathematicians had tackled Benford’s Law over the years, but a solid probability proof remained elusive. In 1961, Rutgers University Professor Roger Pinkham observed that the law is scale-invariant – it doesn’t matter if stock market prices are changed from dollars to pesos, the distribution pattern of significant digits remains the same.

In 1994, Hill discovered Benford’s Law is also independent of base – the law holds true for base 2 or base 7. Yet scale- and base-invariance still didn’t explain why the rule manifested itself in real life. Hill went back to the drawing board. After poring through Benford’s research again, it clicked: The mixture of data was the key. Random samples from randomly selected different distributions will always converge to Benford’s Law. For example, stock prices may seem to be a single distribution, but their value actually stems from many measurements – CEO salaries, the cost of raw materials and labor, even advertising campaigns – so they follow Benford’s Law in the long run. [My bold]

So the key seems to be lots of random samples from several different distributions that are also randomly selected: randomly selected samples from randomly selected populations. Whew, lots of randomness and stuff. Also included is the idea of “scale invariance”: Benford’s Law shows up in certain cases regardless of the units used to measure a property–that’s the “scale” invariance–which implies certain mathematical properties that lead to this behavior with the logarithmic taste to it.

Another interesting aspect of Benford’s Law is that it has found some applications in detecting fraud, particularly financial fraud. Some interesting cases are recounted in this surprisingly (for me) interesting article: Mark J. Nigrini, “I’ve Got Your Number“, Journal of Accountancy, May 1999. The use of Benford’s Law in uncovering accounting fraud has evidently penetrated deeply enough into the consciousness for us to be told: “Bernie vs Benford’s Law: Madoff Wasn’t That Dumb” (Infectious Greed, by Paul Kedrosky).

And just to demonstrate that mathematical fun can be found most anywhere, here is Mike Solomon (his blog) with some entertainment: “Demonstrating Benford’s Law with Google“.

Mar

23

Posted by jns on

March 23, 2009

Rather recently I enjoyed reading Charles Seife’s Sun in a Bottle : The Strange History of Fusion and the Science of Wishful Thinking (New York : Viking, 2008; 294 pages). The subtitle is indicative, although I’m not sure just how strange the history of fusion is.

Of course, what he means by “the history of fusion” is not so much the discovery of nuclear fusion, nor really much about its exploitation to build “H-bombs”. Although these topics appear in early chapters to set the fusion stage, the book is mostly devoted to what happened subsequently on the quest for the practical fusion reactor that would fulfill the dream of “unlimited power”.

Well, the quest still goes on and commercial fusion reactors have been just “20 years away” for at least the last 5 decades. All of the “hot fusion” projects are here: “pinch reactors”, magnetic bottles, Tokamaks, and “inertial-confinement” fusion (the name for those giant, multi-laser devices Lawrence-Livermore labs build to zap deuterium pellets), as well as the “cold fusion” wannabes, including Pons and Fleischmann and the later “bubble fusion”, both of which, in the author’s words, have since been “swept to the fringes of science”.

Anyway, my book note is here, but I thought I’d share this one short excerpt that dramatizes why “people of faith” should never be allowed to set policy: anything they really want to “believe” they end up thinking came from their god. By the way, Lewis Strauss was also the guy who was J. Robert Oppenheimer’s principle antagonist during the struggle to take away Oppie’s clearance as some sort of “punishment” for being too liberal.

The paranoid, anti-Communist Edward Teller was the man who most desperately tried to bring us to the promised land. He and his allies lobbied for more and more money to figure out how to harness the immense power of fusion. Lewis Strauss, the AEC chairman and Teller backer, promised the world a future where the energy of the atom would power cities, cure diseases, and grow foods. Nuclear power would reshape the planet. God willed it. the Almighty had decided that humans should unlock the power of the atom , and He would keep us from self-annihilation. “A Higher Intelligence decided that man was ready to receive it,” Strauss wrote in 1955. “My faith tells me that the Creator did not intend man to evolve through the ages to this stage of civilization only now to devise something that would destroy life on this earth. ” [pp. 59—60]

Mar

22

Posted by jns on

March 22, 2009

I’ve been reading lots of good books this year, several that I can count for my own commitment to the Science-Book Challenge, but I am only now catching up on writing about them. Tonight I wanted to mention a trio of top-notch books from three different domains: cosmology, probability & statistics, and history of science (sort of) / chemistry.

1. John Gribbin, The Birth of Time : How Astronomers Measured the Age of the Universe. The subtitle is exactly the theme of the book, and Gribbin answers the question with a very appealing, very satisfying amount of history and scienticity. I marveled at his writing: he made clear, precise writing seem effortless. (My book note.)

2. Leonard Mlodinow, The Drunkard’s Walk : How Randomness Rules our Lives. Here was an excellent combination of clear and precise exposition of the central ideas of probability and statistics integrated with fascinating examples of those concepts injecting randomness into everyday life. Again, I found the writing very engaging and apparently effortless. (My book note.)

3. Steven Johnson, The Invention of Air : A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America. Again, the subtitle is truth in advertising. The book was sort of an intellectual biography of Joseph Priestly, who got tangled up in the early days of chemistry research and civil unrest and the American Revolution. Mostly successful but still very engaging and satisfying to read. (My book note.)

From Johnson’s Invention of Air, I did set aside a few extra excerpts I wanted to share. Here they are.

This first excerpt sets the tone for the book–and the attitude of the author–but the anecdote is revealing and horrifying to me. Happily, we know that America turned from following this dangerous path that encouraged anti-intellectualism and anti-scientism. I’m sure some would think this just some liberal hyperbole; I don’t.

A few days before I started writing this book, a leading candidate for the presidency of the United States was asked on national television whether he believed in the theory of evolution. He shrugged off the question with a dismissive jab of humor: “It’s interesting that that question would even be asked of someone running for president,” he said. “I’m not planning on writing the curriculum for an eighth-grade science book. I’m asking for the opportunity to be president of the United States.”

It was a funny line, but the joke only worked in a specific intellectual context. For the statement to make sense, the speaker had to share one basic assumption with his audience: that “science” was some kind of specialized intellectual field, about which political leaders needn’t know anything to do their business. Imagine a candidate dismissing a question about his foreign policy experience by saying he was running for president and not writing a textbook on international affairs. The joke wouldn’t make sense, because we assume that foreign policy expertise is a central qualification for the chief executive. But science? That’s for the guys in lab coats.

That line has stayed with me since, because the web of events at the center of this book suggests that its basic assumptions are fundamentally flawed. If there is an overarching moral to this story, it is that vital fields of intellectual achievement cannot be cordoned off from one another and relegated to the specialists, that politics can and should be usefully informed by the insights of science. The protagonists of this story lived in a climate where ideas flowed easily between the realms of politics, philosophy, religion, and science. The closest thing to a hero in this book—the chemist, theologian, and political theorist Joseph Priestley—spent his whole career in the space that connects those different fields. But the other figures central to this story—Ben Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson—suggest one additional reading of the “eighth-grade science” remark. It was anti-intellectual, to be sure, but it was something even more incendiary in the context of a presidential race. It was positively un-American. [p. xiii—xiv]

But there is a lighter side to enjoy here, at least for some of us who can see the humor. I don’t think I have heard any fundamentalists recently who advocated taking lightning rods off churches because they interfere with god’s will. It always strikes me as odd how some science can apparently be perfectly consonant with such an absolutist belief system.

The most transformative gadget to come out of the electricians’ cabinet of wonders was the lightning rod, also a concoction of Franklin’s. [...] Humans had long recognized that lightning had a propensity for striking the tallest landmarks in its vicinity, and so the exaggerated height of church steeples—not to mention their flammable wooden construction—presented a puzzling but undeniable reality: the Almighty seemed to have a perverse appetite for burning down the buildings erected in His honor. [pp. 22—23]

Finally, here is the author quoting Thomas Jefferson writing to Joseph Priestley, after Priestly’s house, scientific instruments, and laboratory notes had all been destroyed by a reactionary mob under the flag of “Church and King”. I think the ironic parallels with our own recent unpleasantness under the previous administration couldn’t be clearer, but the lessons of the Founding Fathers keep getting willfully distorted.

What an effort my dear Sir of bigotry, in politics and religion, have we gone through! The barbarians really flattered themselves they should be able to bring back the times of Vandalism, when ignorance put everything into the hands of power and priestcraft. All advances in science were proscribed as innovations. They pretended to praise and encourage education, but it was to be the education of our ancestors. We were to look backwards, not forwards, for improvement; the President himself declaring in one of his answers to addresses that we were never to expect to go beyond them in real science. This was the real ground of all that attacks you. [pp. 197—198]

Mar

12

Posted by jns on

March 12, 2009

Sir David Attenborough has revealed that he receives hate mail from viewers for failing to credit God in his documentaries. In an interview with this week’s Radio Times about his latest documentary, on Charles Darwin and natural selection, the broadcaster said: “They tell me to burn in hell and good riddance.”

Telling the magazine that he was asked why he did not give “credit” to God, Attenborough added: “They always mean beautiful things like hummingbirds. I always reply by saying that I think of a little child in east Africa with a worm burrowing through his eyeball. The worm cannot live in any other way, except by burrowing through eyeballs. I find that hard to reconcile with the notion of a divine and benevolent creator.”

Attenborough went further in his opposition to creationism, saying it was “terrible” when it was taught alongside evolution as an alternative perspective. “It’s like saying that two and two equals four, but if you wish to believe it, it could also be five … Evolution is not a theory; it is a fact, every bit as much as the historical fact that William the Conqueror landed in 1066.”

[Riazat Butt, "Attenborough reveals creationist hate mail for not crediting God", Guardian [UK], 27 January 2009.]

Mar

11

Posted by jns on

March 11, 2009

Earlier this year I read the book Brian Fagan, The Little Ice Age : How Climate Made History 1300 – 1850, by Brian Fagan (New York : Basic Books, 2000; 246 pages). He takes a close look at the relatively cool period between the “Medieval Warm Period” and the current warming period, and considers in careful but fascinating detail the ways that global climate change affected European society and culture. I thoroughly enjoyed it. I think he did an excellent job assembling all of his facts and dates and locations and keeping them well sorted out and in line with his thesis. I gave it high marks in my book note.

Anyway, here’s an excerpt that interested me. This was one of his many entertaining and enlightening asides, this one a nicely done short history of sunspots.

Sunspots are familiar phenomena. Today, the regular cycle of solar activity waxes and wanes about every eleven. years. No one has yet fully explained the intricate processes that fashion sunspot cycles, nor their maxima and minima. A typical minimum in the eleven-year cycle is about six sunspots, with some days, even weeks, passing without sunspot activity. Monthly readings of zero are very rare. Over the past two centuries, only the year 1810 has passed without any sunspot activity whatsoever. By an measure, the lack of sunspot activity during the height of the Little Ice Age was remarkable.

The seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries were times of great scientific advances and intense astronomical activity. The same astronomers who observed the sun discovered the first division in Saturn’s ring and five of the planet’s satellites. They observed transits of Venus and Mercury, recorded eclipses of the sun, and determined the velocity of light by observing the precise orbits of Jupiter’s satellites. Seventeenth-century scholars published the first detailed studies of the sun and sunspots. In 1711, English astronomer William Derham commented on “great intervals” when no sunspots were observed between 1660 and 1684. He remarked rather charmingly: “Spots could hardly escape the sight of so many Observers of the sun, as were then perpetually peeping upon him with their Telescopes…all the world over.” Unfortunately for modern scientists, sunspots were considered clouds on the sun until 1774 and deemed of little importance, so we have no means of knowing how continuously there were observed.

The period between 1645 and 1715 was remarkable for the rarity of aurora borealis and aurora australis, which were reported far less frequently than either before or afterward. Between 1645 and 1708, not a single aurora was observed in London’s skies. When one appeared on March 15, 1716, none other than Astronomer Royal Edmund Halley wrote a paper about it, for he had never seen one in all his years as a scientist–and he was sixty years old at the time. On the other side of the world, naked eye sightings of sunspots from China, Korea, and Japan between 28 B.C. and A.D. 1743 provide an average of six sightings per century, presumably coinciding with solar maxima. There are no observations whatsoever between 1639 and 1700, nor were any aurora reported.

Feb

27

Posted by jns on

February 27, 2009

Conservation of Energy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics are probably the two most important concepts in physics that have thwarted the aspirations and claims of inventors and charlatans for decades. Someday we hope that the public will understand this.

WEIGHT-LOSS: SCIENCE CONFIRMS THE “PHYSICS PLAN“.

Atkins, Pritikin, Jennie Craig, South Beach, NutriSystem . . . all had one thing in common: they made their inventors very rich. But how could it be that every diet plan seems to work? It’s nothing but consciousness-raising; any plan will make people aware of how much they’re shoveling in. Nine years ago, however, WN came out with the “physics plan.” The plan is based on the Conservation of Energy: “burn more calories than you consume” http://www.bobpark.org/WN00/wn022500.html. Don’t be fooled by cheap imitations. On Wednesday, the New England Journal of Medicine published the results of a two year study of 800 overweight adults. Headed by Frank Sacks of the Harvard School of Public Health, the study confirmed that people lose weight if they cut calories; it doesn’t matter if the calories are fat, carbohydrates, or protein. That, of course, is the WN “physics plan.”

[Robert L. Park, What's New, 27 February 2009.]

Feb

16

Posted by jns on

February 16, 2009

SpaceWeather.com (operated by NOAA) reports that people all over the US are seeing meteors and are concerned that it’s space debris from that dramatic orbital collision between Iridium 33 and Kosmos 2251. Apparently there was also a large meteor seen over Italy that led to similar thoughts.

I’ve also seen reports that the FAA has warned pilots to be on the lookout for space debris, although it’s not clear to me what they’re supposed to do if they see some streaking by except get hysterical.

It’s easy to understand why people will have this reaction, so it’s also useful to note that meteoroids and space debris enter the atmosphere in different–and distinguishable–ways.

Anyway, here is what Spaceweather (for 16 February 2009) had to say about those fireballs:

WEEKEND FIREBALLS: A daylight fireball over Texas on Sunday, Feb. 15th, triggered widespread reports that debris from a recent satellite collision was falling to Earth. Those reports were premature. Researchers have studied video of the event and concluded that the object was more likely a natural meteoroid about one meter wide traveling more than 20 km/s–much faster than orbital debris. Meteoroids hit Earth every day, and the Texas fireball was apparently one of them.

There’s more: On Friday, Feb. 13th, people in central Kentucky heard loud booms, felt their houses shake, and saw a fireball streaking through the sky. This occurred scant hours after another fireball at least 10 times brighter than a full Moon lit up the sky over Italy. Although it is tempting to attribute these events to debris from the Feb. 10th collision of the Iridium 33 and Kosmos 2251 satellites, the Kentucky and Italy fireballs also seem to be meteoroids, not manmade objects. Italian scientists are studying the ground track of their fireball, which was recorded by multiple cameras, and they will soon begin to hunt for meteorites.

Videos, eye-witness reports and more information about these events may be found at http://spaceweather.com.

This is physicist and science-fiction author Gregory Benford. His

This is physicist and science-fiction author Gregory Benford. His