18

Work Makes Heat

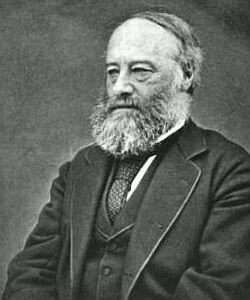

Posted by jns on 18 August 2008 This is British physicist James Prescott Joule (1818-1889), the same Joule who gave his name (posthumously) to the SI unit for energy. Wikipedia’s article on Joule and his most noted contribution to physics is admirably succinct:

This is British physicist James Prescott Joule (1818-1889), the same Joule who gave his name (posthumously) to the SI unit for energy. Wikipedia’s article on Joule and his most noted contribution to physics is admirably succinct:

Joule studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work (see energy). This led to the theory of conservation of energy, which led to the development of the first law of thermodynamics.

At the time that Joule was doing his work, heat was still thought to be caused by the presence of the substance “caloric”: when caloric flowed, heat flowed. That idea was coming under strain thanks largely to new experiments with electricity and motors and observations that electricity passing through conductors caused the conductors to heat up, a notion that proved incompatible with the theory of caloric. This was also still early days in the development of thermodynamics and ideas about heat, work, energy, and entropy had not yet settled down into canon law.

Joule found that there was a relationship between mechanical work (in essence, moving things around takes work) and heat, and then he measured how much work made how much heat, a key scientific step. His experiment was conceptually quite simple: a paddle in a bucket of water was made to turn thanks to a weight falling under the influence of gravity from a fixed height. As a result the water heated up a tiny bit. Measure the increase in temperature of the water (with a thermometer) and relate it to the work done by gravity on the weight (calculated by knowing the initial height of the weight above the floor).

In practice, not surprisingly, it was a very challenging experiment.* The temperature increase was not large, so to measure it accurately took great care, and Joule needed to isolate the water from temperature changes surrounding the water container, which needed insulation. Practical problems abounded but Joule worked out the difficulties over several years and created a beautiful demonstration experiment. He reported his final results in Cambridge, at a meeting of the British Association, in 1845.

Joule’s experiment is one of the ten discussed at some length in George Johnson, The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments (New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2008, 192 pages), a book I recently finished reading and which I wrote about in this book note. It was a nice book, very digestible, not too technical, meant to present some interesting and influential ideas to a general audience, ideas that got their shape in experiments. Taken together the 10 essays also give some notion of what “beauty” in a scientific experiment might mean; it’s a notion intuitively understood by working scientists but probably unfamiliar to most nonscientists.

__________

* You knew that would be the case because people typically don’t get major SI units named after them for having done simple experiments.