07

In Pursuit of the Gene

Posted by jns on 7 July 2008

|

|

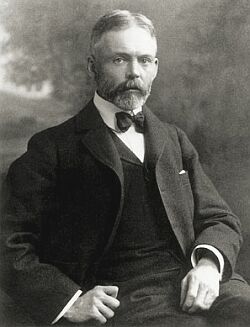

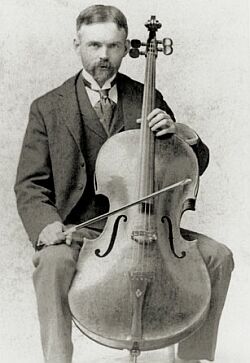

This is geneticist and cellist Edmund Beecher Wilson (1856–1939). On the Columbia University Website, where he is one of their “Living Legacies” (despite his being deceased these last 70 years), he is hailed as the first “cell biologist”, with which history seems agreeable. He spent the bulk of his career at that institution. That “living Legacies” article, “Edmund Beecher Wilson: America’s First Cell Biologist“, by Qais Al-Awqati, is a good appreciation of E.B.Wilson’s work and life, and the source of these two photographs of the younger Wilson.

Early in his research life, just after getting his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins, Wilson became interested in studying the connection between evolution and phylogeny, or phylogenetics (the course of evolution of a species). Later he moved into cell biology and made his greatest discoveries through careful and detailed observation of cell divisions during development, starting with the first division after fertilization of an egg cell by a sperm cell. His work set the course for genetics: the discovery of chromosomes, his own discovery that X and Y chromosomes determine sex (gender), which was a controversial finding at the time, and integrating Mendelian patterns of inheritance into genetics (which wasn’t quite genetics at the time, of course).

Some of this I knew about because I recently finished reading In Pursuit of the Gene : From Darwin to DNA (Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press 2008) by James Schwartz. I liked the book very much, predominantly for these two reasons: 1) it was a thoroughly researched history of the idea of the gene and how it evolved from its earliest (and rather strange) germ of an idea in the theories of Darwin; and 2) author Schwartz actually discussed experiments and their results as a way to comprehend how the idea of the gene made its perilous journey to the modern idea that everyone recognizes and takes for granted. Of course, I wrote a book note.

Even though Schwartz took a biographical approach to telling his story, which he could do largely because the gene-meme almost moved from person to person, as though stepping across a stream on stones, the biographical material were there to serve his main story, that of the idea of the gene. One thing that I did not pick up from Schwartz’ book was Wilson’s love of music, nor the fact that he was a fellow cellist. This is from Qais Al-Awqati’s piece (linked above):

It seems that everybody in Wilson’s family played an instrument. His father played the violin and cello, his mother and sister played the piano (as did both of his aunts), and his brother Charles was a violinist. Wilson began by taking singing lessons, and although he did not have a good singing voice, he says that these lessons left him “with an inveterate habit of reading all of music in do re mi language.” He learned to play the flute, but when he went to Johns Hopkins, he developed a lifelong passion for playing the cello. He wrote, “I was too old to take up so difficult an instrument with any hope of mastering it.” But he eventually became an accomplished cellist and reveled in playing quartets in Bryn Mawr, Philadelphia, and New York.

What a treat: a cute, bearded scientist who was also a cellist! I feel a strange connection across the decades.