20

Astrology Revealed

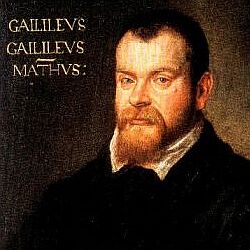

Posted by jns on 20 August 2009 This is the youthful Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who established the intellectual starting point for this short discussion.

This is the youthful Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who established the intellectual starting point for this short discussion.

In Galileo’s day [c. 1610], the study of astronomy was used to maintain and reform the calendar. Sufficiently advanced students of astronomy made horoscopes; the alignment of the stars was believed to influence everything from politics to health.

[David Zax, "Galileo's Vision", Smithsonian Magazine, August 2009.*]

Galileo published The Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius), the book in which he reported his discovery of four new planets (i.e., moons) apparently orbiting Jupiter, in 1610. This business of looking at things and reporting on observations just didn’t fit well with the prevailing Aristotelian view of nature and the way things were done.

Some of his contemporaries refused to even look through the telescope at all, so certain were they of Aristotle’s wisdom. “These satellites of Jupiter are invisible to the naked eye and therefore can exercise no influence on the Earth, and therefore would be useless, and therefore do not exist,” proclaimed nobleman Francesco Sizzi. Besides, said Sizzi, the appearance of new planets was impossible—since seven was a sacred number: “There are seven windows given to animals in the domicile of the head: two nostrils, two eyes, two ears, and a mouth….From this and many other similarities in Nature, which it were tedious to enumerate, we gather that the number of planets must necessarily be seven.”

[link as above]

Science as a an empirical pursuit was still a new idea, quite evidently.

At the time it was understood, for various “obvious” reasons (one of them apparently being that they could be seen), that the planets and the stars in the nearby “heavens” (rather literally) influenced things on Earth. There was no known reason why or how, but this wasn’t a big issue because causality‡ didn’t play a very large role in scientific explanations of the day. Recall, for instance, that heavier objects rushed faster to tall to Earth because it was their nature to do so.

What I suddenly realized awhile back (I was reading the book by Robert P, Crease, Great Equations, but I don’t really remember what prompted the thoughts) is the following.

Received mysticism today claims that astrology, the practice of divination through observation of the motions of the planets, operates through the agency of some unknown, mysterious force as yet unknown to science. Science doesn’t know everything!

But this is wrong. In the time of Galileo there was no known “force” to serve as the “cause” for the planets’ effect on human life, but it seemed quite reasonable. In fact, the idea of “force” wasn’t yet in the mental frame. The notion of “force” as it is familiar to us today only began to take shape with the work of Isaac Newton c. 1687, when he published his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which contained his theories of mechanics and gravitation, theories where the idea of “force” began to take shape, and to develop the ideas of causality.

But the notion that there is no known mechanism through which astrology might work we now see is wrong. The mechanism, arrived at by Newton, which handily explained virtually everything about how the planets moved and exerted their influence on everything in the known universe, was that of universal gravitation.

The one thing that universal gravitation did not explain was astrology. But even worse, this brilliant theory showed that the universal force behind planetary interaction and influence was much, much too small to have any influence whatsoever on humans and their lives.

Newton debunked astrology over 300 years ago by discovering its mechanism and finding that it could not possibly have the influence that its adherents claimed.

Some people, of course, are a little slow to catch up with modern developments.

———-

* This is an interesting article that accompanies a virtual exhibit, “Galileo’s Instruments of Discovery“, adjunct to a physical exhibit at the Franklin Institute (Philadelphia).

‡ Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that our modern notion of causes was quite a bit different from 15th century notions of causes.